December 4, 2025

Fierce optimism despite challenging circumstances

Reflecting on nearly three decades of IAVI Report and the future of HIV vaccine research.

By Kristen Kresge Abboud

In a perfect world, the final IAVI Report article would commemorate the successful deployment of a highly effective, affordable HIV vaccine in all the places and populations where it is most needed.

It is, however, far from a perfect world.

War, food insecurity, the effects of climate change, existing epidemics including HIV/AIDS, as well as the promise of future pandemics, are either threatening or destroying the lives and livelihoods of millions of people around the world. Simultaneously, the political commitment to global health and investment in biomedical research, both in the U.S. and abroad, is faltering.

Over the last year, funding for many global health research efforts has diminished or disappeared altogether. In January, the U.S. withdrew its support for the World Health Organization, a blow that is causing the organization to cut a quarter of its workforce, according to recent reports. And earlier this year, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) was dismantled and 83% of its programs were terminated. This could have devastating effects, with some studies suggesting a “staggering number” of avoidable deaths could occur by 2030 if these cuts aren’t reversed. USAID cuts also left many researchers, collaborations, clinical trial networks, and non-profit organizations engaged in public health research in a lurch.

Several European governments are also reducing their investment in global health as they prioritize national security and defense budgets due to the ongoing war in Ukraine and other geopolitical concerns. What some have coined the “golden age” of global public health — a period from the 1990s to the early 2020s marked by a dramatic increase in funding, new partnerships, and unprecedented innovation — seems to be coming to an end.

Vaccines, one of the greatest public health achievements of all time, are far from immune (pardon the pun) to budget cuts, reprioritization, and disinformation campaigns. The U.S. funding for Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, which historically accounted for a substantial portion of the organization’s budget, is set to be cut entirely next year, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Today, instead of science being lauded, it is, in some circles, being denigrated.

IAVI Report cover, 2010

Medical research writ large and vaccine research, in particular, are also under scrutiny. The U.S. government slashed research funding for mRNA-based vaccines, the platform behind two of the COVID-19 shots that helped save tens of millions of lives globally. Research grants from the U.S National Institutes of Health (NIH) have been cut drastically, and research budgets at many universities are also shrinking. A report in JAMA Internal Medicine finds that one in 30 clinical trials, involving more than 74,000 participants, were affected by disruptions in NIH grant funding. These trials were primarily focused on infectious diseases, prevention, and behavioral research.

All of this is sobering, to say the least. Yet, when I survey the nearly 30 years of IAVI Report, and its sister publication VAX, I see fierce optimism despite harrowing circumstances.

Within the thousands of articles in these two IAVI publications, there are stories of scientists, researchers, nurses, community outreach workers, activists, clinical trial volunteers, and many others who have faced monumental challenges yet remained steadfast in their dedication to ending AIDS. Their efforts are inspiring, and sharing them with our readers was both a joy and a privilege.

As a result of this commitment and dedication, HIV was transformed from a death sentence into a chronic infection. In 2021, commemorating the fortieth anniversary of the first descriptions of what would become known as AIDS, Anthony Fauci, former head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), reflected on this accomplishment. “In 1985, a 25-year-old in the United States diagnosed with AIDS had a life expectancy of less than two years. Today, a person with HIV can expect to die in old age, of other causes.” An astonishing feat of science.

This eventually became a reality for people living with HIV around the world, but only because a coalition of activists united to ensure accessibility to these life-saving medications and demanded accountability from governments and companies to provide these drugs free or at an affordable price — an astonishing feat of activism. In 2005, I interviewed the renowned South African activist Zachie Achmat, and it is difficult to think of a more poignant example of someone who believed in and fought for equal access to life-saving HIV treatments.

Over the three decades of IAVI Report issues, there was something for everyone — interviews with scientists, Nobel laureates, and even HIV research couples; profiles of artists who used the virus as their inspiration; summaries of conferences near and far that tracked progress and contextualized the research efforts in HIV prevention research as well as for other infectious diseases; articles that tracked the progress of major consortia and partnerships that were built to advance HIV research; stories that heralded the clinical and scientific research capacity among researchers in Africa and India; as well as news pieces detailing advances all the way from the molecular to the global level. Behind these stories, there was a common thread — the passion, persistence, and ingenuity of people whose careers or lives were dedicated to battling HIV/AIDS and other infectious diseases across the globe.

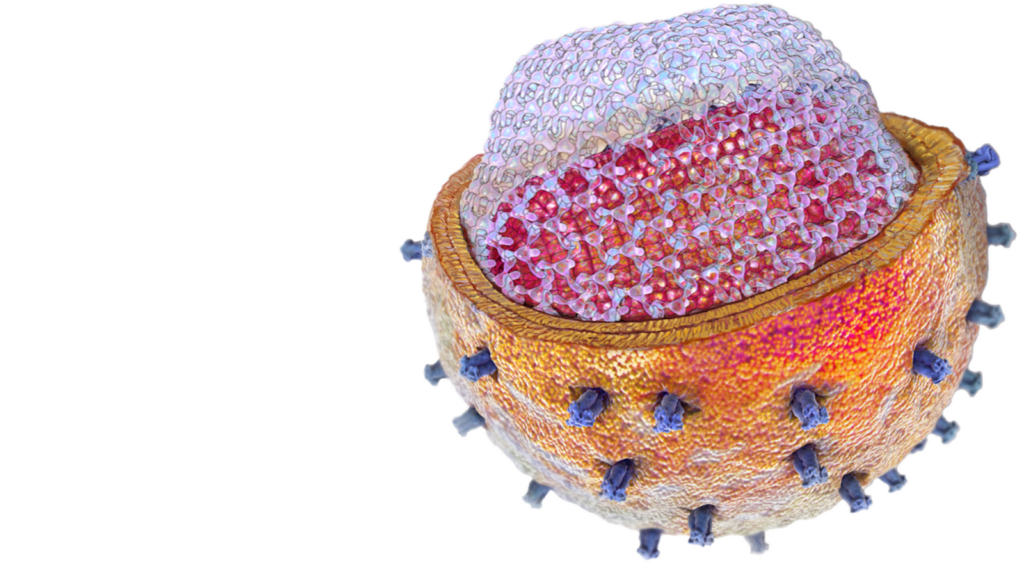

Many IAVI Report articles describe scientific triumphs. These triumphs include the successful development of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP; both oral and more recent long-acting injectable versions), and the development of vaccines for other infectious diseases, among them SARS-CoV-2, respiratory syncytial virus, and human papillomavirus. In addition to the stories on HIV prevention and cure research, we’ve been able to write about the many peripheral benefits of this work, including how it has improved pandemic responsiveness, provided a better understanding of human immunology, and accelerated advances in structure-based vaccine designs that will benefit all future vaccine development, as well as improve the prospects for targeted cancer immunotherapies.

And, yes, there were also many other stories recounting the numerous setbacks in the effort to develop an HIV vaccine. Several large-scale trials inspired hope but never yielded a successful product. Instead, these results often sent researchers back to the drawing board, or rather, the laboratory bench.

IAVI Report cover, 2019

Eventually, the field coalesced around the need for vaccine-induced broadly neutralizing antibodies, and researchers started developing stepwise strategies to engineer vaccine antigens that could induce them. These are no longer “shots in the dark,” rather, vaccine candidates designed specifically to initiate and mature the exact types of broadly neutralizing antibody responses against the virus that studies indicate could be protective if present at high enough concentrations.

Today, the HIV vaccine field is beginning to see the fruits of those efforts.

We asked experts in the field to share their thoughts on the current trajectory of HIV vaccine research. What we found is that many of them view the prospects of developing an HIV vaccine as more promising today than ever before. Optimism alone doesn’t guarantee success. Persistence will also be critical. Although the field is on a promising path, experts still view the inherent scientific challenges and diminished funding as two of the biggest barriers to HIV vaccine development. However, the history of HIV/AIDS shows that these are not insurmountable problems.

Only a small percentage of the experts we surveyed think an HIV vaccine is unlikely to be developed, and an overwhelming majority of experts who responded to our queries say an HIV vaccine is still necessary, even in the era of lenacapavir, a long-acting injectable antiretroviral that is 96-100% effective in preventing HIV acquisition. In a perspective piece in the New England Journal of Medicine earlier this year, researchers acknowledge that lenacapavir raises the bar for an HIV vaccine but certainly doesn’t eliminate its value. They write: “Only an approach that combines these interventions will end the HIV epidemic.”

Some argue that the need for an HIV vaccine remains as strong today as it was in the 1990s when IAVI Report began. “Gravely, one of the core epidemiologic features of HIV is that over 40% of cases in the global north emanate from persons who do not self-identify as high risk. This figure is nearly 70% in countries with endemic epidemics, like South Africa,” says Larry Corey, co-principal investigator of the HIV Vaccine Trials Network. “These large swaths of the population are not candidates for short or long-acting antiretrovirals and are the focus of why an HIV vaccine is needed to produce an AIDS-free generation.”

It is unfortunate to see IAVI Report end at a time of such optimism. The publication filled a unique niche in the field. It aimed to be a publication for scientists; a place they could find context for and analysis of current research trends. Its other goal was to provide content that was accessible to those without specialized knowledge or training. It was a difficult balance, but one that the publication did artfully.

IAVI Report cover, 2019

When I started writing for IAVI Report in 2005, I worried that the subject area was too narrow. That I’d run out of stories to tell. That was never the case, and 20 years later, it still isn’t. HIV remains one of the most difficult-to-combat pathogens ever known. Writing about HIV prevention efforts, whether through vaccination, passive administration of monoclonal antibodies, or long-acting PrEP, sparked my interest in countless areas of biology, immunology, vaccinology, and public health policy. It widened my horizon rather than narrowing it, and it is my sincere hope that it did the same for you. It gave me an understanding of and appreciation for the people who dedicate themselves to making the world a healthier, safer place.

There are many people to thank for their enduring support of IAVI Report, starting with those within the organization who recognized the value of scientific communication from the start and made this publication one of IAVI’s earliest initiatives. Over the past 30 years, many individuals within IAVI championed and defended the publication’s independence, which allowed us to earn and maintain the respect of the scientific community.

And, of course, none of this would have been possible without the devoted supporters of IAVI Report outside the organization, particularly IAVI’s donors, including USAID, that believed in the power of disseminating accurate scientific information to engage and mobilize communities of scientists, researchers, and advocates across the globe.

We are also incredibly grateful for the countless sources we called for interviews or expert guidance, time and time again, to ensure we presented the complex and constantly evolving science as accurately as possible. This, too, was vital to the publication’s reputation and reach.

Finally, we are thankful for you, our loyal readers, who shared your feedback willingly and kept interest in this work alive.

In this final article of IAVI Report, we can’t end with the success story of an HIV vaccine. But we can leave you with the enduring optimism that is woven through our 30 years, often in challenging circumstances. In the words of Marie Curie: “… the way of progress is neither swift nor easy.”

We certainly don’t live in a perfect world, but we can all strive to make it somewhat more so.

Thank you for sharing your stories and reading ours these past 30 years.