October 23, 2025

‘Of all the moments for science to slow down, this is not it.’

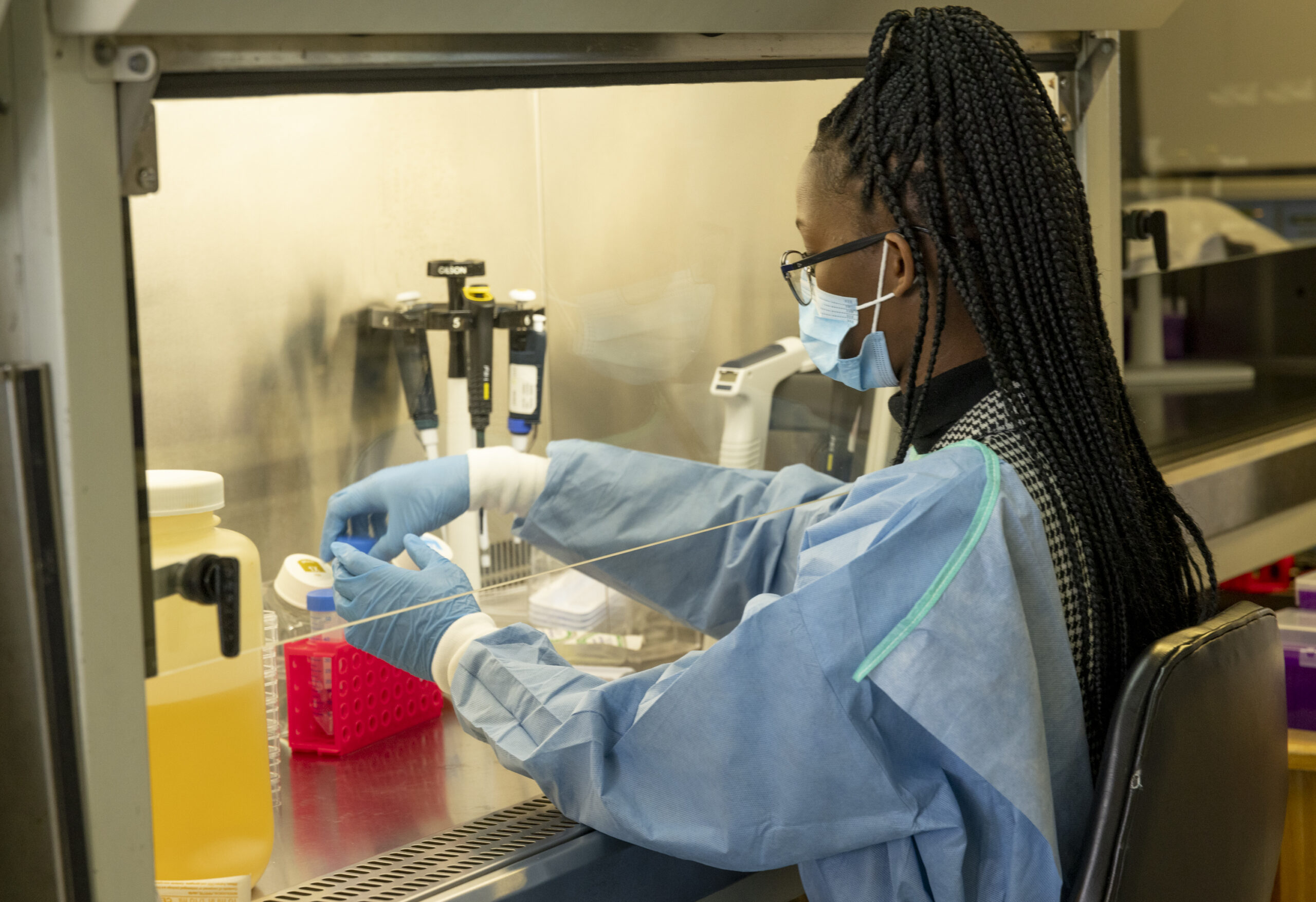

An HIV vaccine academy showcases the scientific talent of African researchers but is tempered by funding worries

By Michael Dumiak

This past June in Cape Town, Glenda Gray, chief medical officer at South African Medical Research Council and distinguished professor, Infectious Disease and Oncology Research Institute, University of the Witwatersrand, joined fellow experts for the semiannual HIV Vaccine Science Academy sponsored by the International AIDS Society, the Gates Foundation, and the emerging infectious disease arm of the French research institute INSERM. The meeting brings together young and mid-career researchers based on the African continent for expert tutelage and scientific exchange.

The splintered and precarious state of research funding was definitely on the agenda, but the real focus, Gray says, was on maintaining HIV vaccine and prevention research in Africa and finding ways to support the talent and capabilities in both emerging and established research labs across sub-Saharan Africa. “It’s not a good time to be a young scientist interested in HIV vaccines,” says Gray. “But the people here seemed quite well supported, skilled, and with a lot of potential.”

Over three days, the group explored avenues for funding and grant writing, discussed how to use artificial intelligence in their lab practices, and hammered out the nuts and bolts for structuring studies on T-cell immunity. Researchers hailed from Nigeria, Zimbabwe, Ghana, Mozambique, Kenya, Zambia, and Uganda with a range of pursuits, and all armed with research proposals.

“We had a researcher there working with placentas who had some fascinating insights,” Gray says. “I said to her that there’s so little known about placental immunology, so even beyond focusing on HIV, you could be a placental immunology expert. It bears on mother-to-child transmission, the traffic of antibodies across the placenta, the role of inflammation, and it is a field that is wide open.”

This type of ingenuity is what many researchers are looking for as they seek to fill funding holes left by the drastic cuts in U.S. government funding for HIV/AIDS research.

Gray herself is enduring one of the most turbulent years in recent memory. In February, she and dozens of colleagues in the BRILLIANT consortium (of which she is program director) were poised to start a multi-armed clinical study of HIV vaccine candidates at sites in South Africa, Nigeria, Kenya, Mozambique, Zambia, Uganda, Zimbabwe, and Tanzania. Then came the dismantling of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), underwriter of BRILLIANT.

It upended those grand plans, but Gray and her colleagues are keeping the research effort alive, if barely. One trial site remains operational thanks to funding from the Gates Foundation and donated vaccines from the developers. “It’s not the kind of multi-centered, multi-country study we wanted to do, but it allowed us to continue with discovery and oil the system,” Gray says.

The virologist Penny Moore, academic head of the Divisions of Virology and Immunology at the University of the Witwatersrand and National Institute for Communicable Diseases, is a Johannesburg-based colleague of Gray’s, and one of the principal researchers within BRILLIANT. Like Gray, she fluctuates between gloom and marveling at the fine local talent and research capabilities, as well as how far and fast it’s all developed.

“It’s extraordinary what has been built across Africa,” Moore says. The tools that made such a difference during the COVID pandemic — the basic virology, epidemiology, sequencing, and clinical trial expertise — benefited from and were, in many ways, first built and developed to support HIV research. The COVID surveillance network in South Africa, for instance — Next Generation Sequencing South Africa, or NGS-SA — came out of the national health sequencing systems established to monitor HIV and antiretroviral drug resistance, Moore says. Wastewater-based surveillance, which also began during the COVID-19 pandemic, has now expanded to screen for infectious diseases like measles and HIV, and it’s all done locally.

Gene sequencing capabilities under the aegis of the nearly decade-old Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) have greatly expanded, with the goal of the Africa Pathogen Genomics Initiative to expand the skilled workforce at the genomics and bioinformatics center in Addis Ababa and among member states, and to share genomic data via robust pathogen archiving platforms. The organization has set up coordination centers in Gabon, Kenya, Nigeria, and Zambia to support this work.

Advanced analytical research tools and capabilities are also much more established at a local or at least regional level, Moore says, marking what she calls a fundamental shift from dependence on external technical assistance to using African know-how to conduct pathogen surveillance and analysis. “It’s not just the ability to sequence, it’s the ability to interrogate our own data that now exists across tens of countries in Africa, as opposed to only a handful five years ago,” she says.

These capabilities extend to basic science efforts that demand highly advanced skills and laboratory functions. Moore and her partners contributed to ongoing experimental trials aimed at developing germline-targeting immunogens for HIV vaccine candidates, a direction spearheaded by immunologist William Schief at Scripps Research and IAVI, who is now also Vice President of Protein Design at the company Moderna.

“The vaccine field requires really top-tier immunology and the ability to sort individual B cells and sequence them and be able to say, that’s a good response or that’s not a great response. And that can all now be done in Africa,” Moore says.

Which is why, like Gray, she doesn’t only despair. Though there still is plenty of that.

“It is hugely stressful. Every lab meeting used to be focused on data, data, data. Now they all start with an update on the funding situation — which grants have been cut and which programs we should no longer be pursuing. It starts with me reassuring people that I am telling them everything I know and will continue to do so,” she says. “The stress that people have with whether their jobs are secure, it’s hugely exhausting for everyone, especially the most junior folks.”

There is also the stress of ending promising projects. Moore contributed to research findings published earlier this year by the South African Medical Research Council’s Gerald Chege and the University of Cape Town’s Rosamond Chapman on testing an HIV vaccine formulation in monkeys. The experiments were done in Parow Valley, in suburban Cape Town. “Right now, there’s no easy way to do non-human primate studies in Africa; there are very few facilities,” she says. “What we wanted to do was to use African green monkeys, which are super common in this part of the world. Being able to use them as models of immunogenicity seemed really appealing, much better than some of the other models we tend to use.” But this effort was supported by USAID, and when that funding was pulled, the green monkey idea was iced.

Moore says it is difficult to watch this all happen when she feels like HIV vaccine research and development is showing such promise. “I still feel we’re on the right path,” she says. “I feel like the immunology, virology, and vaccinology are right there. It feels like of all the moments for the science to slow down, this is not it.”

The young and mid-career fellows gathered at the HIV vaccine academy feel similar pressure to keep their own research going and to find the funding to do so.

After the close of the academy in Cape Town, Chizaram Onyeaghala returned home to Port Harcourt, Nigeria. A few weeks later, he presented a poster at the 13th International AIDS Society Conference in Kigali, Rwanda. The poster was based on his mpox diagnosis in a newborn baby who had acquired the virus via either transplacental or postnatal transmission. Pediatricians had suspected molluscum contagiosum, another poxviral disease and a common one, but Onyeaghala was quickly able to get a DNA test at Port Harcourt to confirm otherwise. He is a young infectious disease clinician, runs a large HIV treatment clinic, and has published research on Lassa fever outcomes and mpox epidemiology. Last year he went for training to the Centre for Epidemic Response and Innovation or CERI, Tulio de Olivera’s genomics and bioinformatics facility in Stellenbosch, South Africa.

Onyeaghala is still charting his course and scrambling to keep the PEPFAR-funded HIV clinic on track in Port Harcourt. But he knows he wants to keep pursuing research and doesn’t think he necessarily has to leave Africa to do so. “I love the United Kingdom, but I love infectious diseases even more,” he laughs. “For me it’s not so much about Global South, Global North. It’s more about the organizations and how much reach they have. You can have organizations in the Global South that reach very deep and wide.”

Across the continent in Zimbabwe, Arthur Vengesai seeks ways to investigate and design mRNA-based vaccines tailored for resource-limited areas where production and distribution are difficult. With the Africa CDC setting a target for 60% of vaccine manufacturing to come from local sources by 2040, he will have opportunities to use that expertise, so he attended the HIV vaccine academy to buff his trial management expertise.

It’s a pressing topic: at the World Health Summit in Berlin in mid-October, one of the oversubscribed sessions was on the state of vaccine manufacturing in sub-Saharan Africa. “In 1999,” said Shanelle Hall, an advisor to the Africa CDC, “I began procuring vaccines for India. At that point, we could not imagine a world where there was one, maybe even more than one vaccine manufacturer in India. And we were in a vaccine crisis. Now, we cannot imagine a world where vaccine manufacturers are not in India.” She sees the same for Africa. “This was a big market shaping, but it is also our imagination. It’s where we want to set our eyes.”

Today, researchers and scientists across Africa are setting their eyes on sustainable funding that will allow them to continue their work on HIV and beyond.