October 23, 2025

Dedication, not defeat

Drastic cuts to U.S. government funding imperil HIV/AIDS treatment and prevention programs and threaten HIV vaccine and cure research efforts across Africa. But the overarching view from East African researchers is one of resilience, not defeat.

By Kristen Kresge Abboud

My first reporting trip to Africa was 16 years ago. I was in Cape Town for the 5th International AIDS Society Conference and to visit several clinical research centers, vaccine trial sites, and laboratories in and around the coastal city, as well as in Johannesburg.

This was my first opportunity to witness IAVI’s collaboration with the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) in action. I was able to meet scientists, nurses, and community workers whose dedication to HIV/AIDS research was unparalleled, and to see the physical infrastructure and human capacity that these types of decades-long partnerships could help build, enhance, and sustain.

I will never forget these experiences. I visited the HIV research unit at the Desmond Tutu Health Foundation, the first public clinic in South Africa to make antiretroviral therapy available. I attended a press conference at which a South African Muppet with HIV interviewed Nelson Mandela. It may sound silly — a former president, humanitarian, and legendary HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis advocate being interviewed by a puppet — but it wasn’t. It was moving. Awe is an overused term, but, on this trip, I often felt awed by the work on HIV/AIDS that I had previously only understood from thousands of miles away.

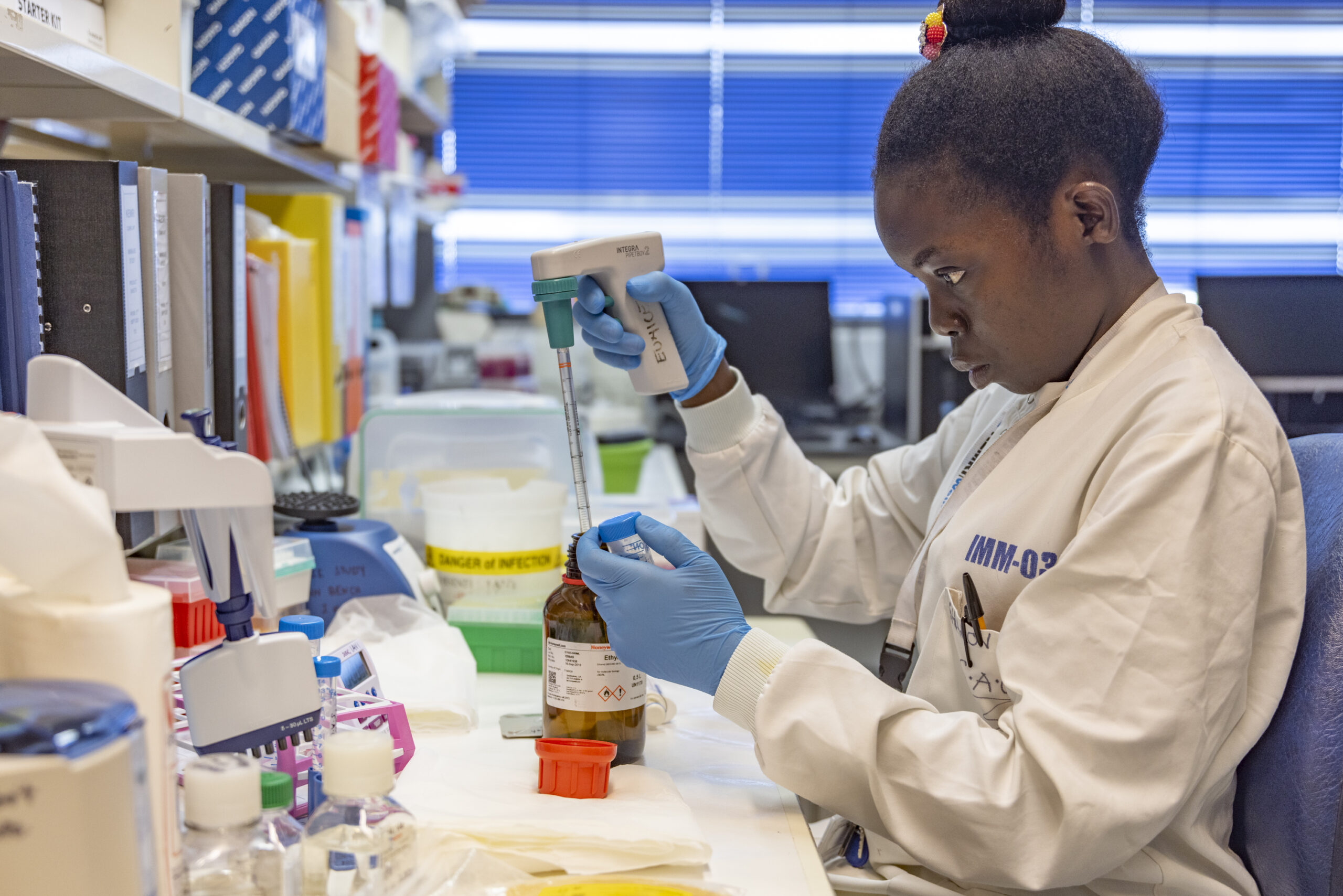

Several years later, I was able to visit other clinical research centers in Kenya, both in and around the capital city, as well as in the coastal towns of Mombasa and Kilifi. These centers were all operated in partnership with local organizations, among them the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI), Kenya AIDS Vaccine Initiative (KAVI) Institute of Medical Research, and the University of Nairobi. In partnership with several international organizations, including Wellcome, IAVI, and the European and Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership (EDCTP), these institutions established world-class clinical research centers capable of conducting trials of HIV vaccines and other modalities that were beyond impressive. The staff at these sites pioneered community outreach and engagement efforts, led pivotal epidemiological studies to inform future vaccine design, conducted disease surveillance that illuminated viral properties and transmission dynamics in different populations, and established the laboratories and expertise required for basic science efforts applicable not only to HIV but also to other infectious and non-communicable diseases.

On another trip to Africa, I visited the clinical research center led by the Rwanda Zambia Health Research Group in Lusaka, Zambia, when the center was actively involved in the Imbokodo HIV vaccine trial. It was my first time at a center while a Phase 2b efficacy trial was underway. The talent, dedication, and optimism of the researchers, investigators, community outreach workers, and volunteers at that center were palpable and inspiring.

The people I met on each of these trips had stories to tell. Some were about the obstacles they faced in doing this work and the small and large victories they amassed. Much of my writing focuses on the scientific/technical barriers to HIV vaccine and prevention research, but that is only one dimension. These individuals had to overcome many more obstacles: threats of physical violence, protests that shut down their sites, power outages that threatened the viability of their samples, vaccine and HIV misinformation campaigns, among others. Through it all, they remained resilient.

The expert staff, the buildings and laboratories they work in, and the networks and partnerships they helped build over the past 25 years are a living monument to this resilience, which is once again being tested.

There is much to say and write about the sudden and dramatic cuts to USAID, the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), and other global health efforts funded by the U.S. government, and there will be even more to say once the impact of these cuts on HIV treatment and prevention programs is fully realized. But that isn’t what this story is about. Or, at least, it isn’t only about that. Over the past several weeks, my colleague Michael Dumiak and I spoke with several African researchers about the future of their programs and their determination to apply the expertise they have built to continue advancing scientific discovery and progress on the continent. The scientific prowess of these researchers and their tenacity live on. The work may become more difficult, but it won’t stop.

With time comes perspective

March was a low point, Marianne Mureithi recalls. Early that month, researchers gathered for the annual Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI), a major event on the calendar for HIV/AIDS scientists and clinicians.

Mureithi, Director of the Kenya AIDS Vaccine Initiative-Institute of Clinical Research (KAVI-ICR) at the University of Nairobi and former chair of the Department of Medical Microbiology and Immunology, felt the sense of loss that permeated CROI following major cuts in the U.S. government funding for global health research, including drastic cuts to PEPFAR and a near complete dismantling of USAID.

“It was a very different meeting. First of all, many people cancelled their trip because their funding or the sponsorship was pulled,” she says. “We had demonstrations and banners that read: Science still matters. HIV still matters. There was a feeling of shock and horror.”

But by July, the mood shifted. At the 13th International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Science in Kigali, Rwanda, the somber feelings of CROI had somewhat subsided. “At IAS, I saw a lot of resilience and a lot of positivity,” says Mureithi. “You can’t kill something that is true, honest, data-driven, and that matters to the people. There was good science being presented, including talks on HIV cure research, and good news on lenacapavir [the long-acting injecting antiretroviral that is highly effective at preventing HIV acquisition] and other interventions.”

Mureithi was a co-investigator of IAVI’s ADVANCE (Accelerate the Development of Vaccines and New Technologies to Combat the AIDS Epidemic) program, which was supported by USAID through PEPFAR. Earlier this year, due to USAID cuts, the ADVANCE program ended prematurely, leaving many of its grantees, including Mureithi, scrambling to fill this gap.

In a sense, she was fortunate. Mureithi already receives diverse funding, including grants from the Gates Foundation, the German Research Foundation or DFG, the UK Research and Innovation-South Africa Medical Research Council partnership, Gilead Sciences, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), the National Institute for Health and Care Research, Wellcome, and SANTHE (sub-Saharan African Network for TB/HIV Research Excellence), among others. These grants are allowing her team to continue ongoing work at KAVI-ICR. But there are still gaps to fill, and Mureithi seems well-positioned to do so. She is starting by collaborating closely with the African-led research networks that ADVANCE helped establish. “I’m just grateful to IAVI for bringing these groups together so that we can work collaboratively,” she says.

As Director of KAVI-ICR, Mureithi’s immediate goal is to ensure sustainable funding and strategic growth across the institute’s research portfolio. This includes advancing work on HIV prevention and cure, strengthening collaborations in immunology and emerging infectious diseases, and expanding into new areas of translational and community-driven health research. Her best piece of advice to other African researchers is to focus on collaboration and diversification. And to remain positive. “I think we’re growing stronger as a result of this because we are forming new alliances and finding new ways to do science,” she says.

Not everyone may share her level of optimism, but Mureithi sees several potential upsides to the current U.S. funding cuts. She wonders whether worries over research funding in the U.S. might lure African researchers back to the continent, reversing the brain-drain phenomenon. “We want to see Africa’s science and problems being addressed by African scientists. There is still a vibrant research community here despite the funding cuts, and I think when we are all working as a team, we can overcome these challenges,” she says.

Mureithi thinks the withdrawal of U.S. government funding might also spur more domestic investment in scientific research in her country. After the collapse of USAID, she heard from several friends who were surprised to find out how much Kenya relied on U.S. government support. “They were shocked to learn that Kenya is almost 100% dependent on foreign assistance, even for things like preventing mother-to-child transmission of HIV, and then they started asking hard questions about why we can’t fund this type of work on our own. How much of our GDP [gross domestic product] can we give back to research, or use to take care of patients, or even provide simple things such as bed nets for malaria prevention?”

The goal of the ADVANCE program was always for local institutions to take leadership of these programs and for domestic budgets to gradually fund them independently. This process is just happening much more abruptly than anyone had expected or prepared for. “On a positive note, it’s sparked a national conversation about how we cannot be donor dependent. It’s really challenging the healthcare system and the government to consider how we can restructure to be able to fund these efforts,” Mureithi says.

Advancing research

In the Kenyan coastal town of Kilifi, Eunice Nduati finds herself in a similar situation. Nduati, an immunologist at the KEMRI-Wellcome Trust Research Programme, is working to sustain and expand the scientific efforts she and her colleagues initiated in support of HIV vaccine research and development as part of ADVANCE.

Fortunately, she is also poised for success. As an ADVANCE co-investigator, Nduati led the immunological analyses of a recent HIV vaccine trial conducted by IAVI and its partners in Kenya, Rwanda, and South Africa. This trial, known as IAVI G003, was groundbreaking, both because it tested one of the next-generation HIV vaccine candidates via an mRNA delivery system and because the complex immunological endpoint analyses for the trial were all conducted in Africa.

The vaccine candidate was an engineered nanoparticle designed to initiate the complicated, stepwise process of inducing broadly neutralizing antibodies, the type of immune response researchers now think is required for an effective vaccine. The goal of the trial was to characterize the immune responses induced by this immunogen in elaborate detail to determine if it effectively kicked off the process of engaging and maturing specific B cells.

Nduati and her colleagues, working alongside scientists from Scripps Research and the IAVI Neutralizing Antibody Center lab in La Jolla, California, conducted single-cell analysis of the B-cell receptors at her lab in Kilifi as well as binding antibody multiplex assays at laboratories at KAVI-ICR. All the work was done within Kenya on state-of-the-art equipment.

“This was not service provision or being directed on what to do. It was more like a co-creation. The funders, the international collaborators, and our institution were all working together to co-create this work,” says Nduati.

This experience is likely to have a lasting impact, far beyond the conduct of that one trial or the ADVANCE program itself. “This provided us with an opportunity to be at the front lines of what is happening within the field. Working on the cutting-edge IAVI G003 analysis provided us with significant visibility and highlighted the types of science we can conduct on the continent. That was quite beneficial,” says Nduati.

There may not be a better example of ADVANCE in action than this. As the HIV vaccine field shifted its focus to more discovery work, focusing on the design and development of vaccine candidates that could induce long-sought-after broadly neutralizing antibodies against the virus, the ADVANCE program and its architects at USAID and IAVI wanted to bring more of the basic science and translational work to the clinical research centers where these candidates were being tested in Africa and India. The goal was for researchers at these sites to actively participate in conducting clinical trials as well as in analyzing the results and helping to reformulate improved vaccine candidates for further testing. Devin Sok, Operating Partner and Head of Science at the non-profit Global Health Investment Corporation, was at IAVI at the time and helped orient ADVANCE’s science program in close partnership with African researchers and USAID.

“At the time, there was a lot of work being done in the West in these more well-resourced labs to generate data and design vaccine immunogens. And it just felt like it was the right time not just to hand off vaccine candidates but to have equitable engagement with these clinical research centers,” Sok recalls.

This didn’t happen overnight. Sok and his colleagues at Scripps, IAVI, and USAID invested extensive time and resources into mentoring the existing talent among scientists at the partner sites in sub-Saharan Africa and enhancing the laboratory infrastructure, so the equipment was available to do these types of analyses.

This investment paid off. As a result of this trial, these centers and scientists proved they can participate as equal collaborators in translational research, applying insights from clinical trials to inform the basic discovery science that could lead to an eventual vaccine. “I think now there is recognition from the broader ecosystem that a different way of engaging with scientists in sub-Saharan Africa has been created,” adds Sok. “It’s really just about equipping talented scientists with the same resources so that you level the playing field.”

Nduati is grateful for what this sustained investment and commitment have provided her and her team. “I’d like to take the opportunity to thank USAID for the funding that they provided because that helped us create the structural capacity, buy equipment, and set up these platforms that now can support various aspects of our work,” says Nduati. “Building a scientific career doesn’t take five years — it’s something that is really long-term. And we’ve been fortunate to have a lot of long-term investment in building scientific capacity through working with IAVI through ADVANCE, as well as within our institution, the KEMRI-Wellcome Trust Research Programme, to enhance the capabilities of our scientists.”

This cross-cutting capacity is what Nduati hopes will propel her and her team to more funding opportunities now that ADVANCE has ended. Last year, Nduati’s center was awarded funding from the Gates Foundation to expand its work on immunological endpoint analyses for vaccine trials. Her team is also part of a consortium that receives funding from the Wellcome Trust Discretionary Award to expand single-cell analysis in Africa and contribute to the Human Cell Atlas, a global consortium that aims to map every cell in the human body.

The problem is that all the groups that lost U.S. government funding are now competing for the same grants, making it more challenging to identify ways for them to sustain their research. This is particularly vexing to William Kilembe, Project Director at the Center for Family Health Research in Lusaka. “Even as a strong network and institution, it becomes almost impossible to win these grants,” he says.

Unlike the discussion in Kenya around domestic funding of research or basic science endeavors, Kilembe says the focus in Zambia is on more pressing needs. “What I’ve seen in Zambia is mainly discussion around how to continue providing HIV care because that’s the immediate challenge. Questions about funding research will not be a top priority,” he says.

Community engagement will also be hampered as a result. This puts his center, which is primarily oriented toward clinical research, in a precarious situation. Without HIV vaccine candidates to test, it becomes difficult to conduct outreach to policymakers or to communities about the importance of this work. The site is involved in an ongoing TB vaccine study, which Kilembe says was a “lifesaver” in terms of maintaining operations and site staff. “We are a non-governmental research organization and are heavily dependent on grants and donor funds, and if that funding can’t be sustained, it becomes difficult to maintain the institution in its current form,” he says.

But Kilembe, who served as a principal investigator on several HIV vaccine studies, is no stranger to adversity. “We are actively looking for new opportunities and collaborations, and we remain hopeful.”

Hope is a word I heard quite often in these discussions.

“The funding from USAID and IAVI gave us a foundation. It gave us a house. It’s now up to us to ensure that our house survives. It’s not all doom and gloom,” says Mureithi. “There’s still hope.”