September 12, 2025

Frequently asked questions: Lassa fever

Learn more about Lassa virus, a zoonotic virus that causes severe hemorrhagic fever in humans.

Exactly what is Lassa fever? Lassa virus (LASV) causes seasonal outbreaks across West Africa, and the World Health Organization (WHO) has identified it in the Pathogen Prioritization framework as a top emerging pathogen likely to cause public health emergencies of international concern. IAVI and our partners are developing a single-dose LASV vaccine candidate as part of our emerging infectious disease (EID) vaccine development program. Read more about our Lassa fever vaccine development program.

Frequently asked questions

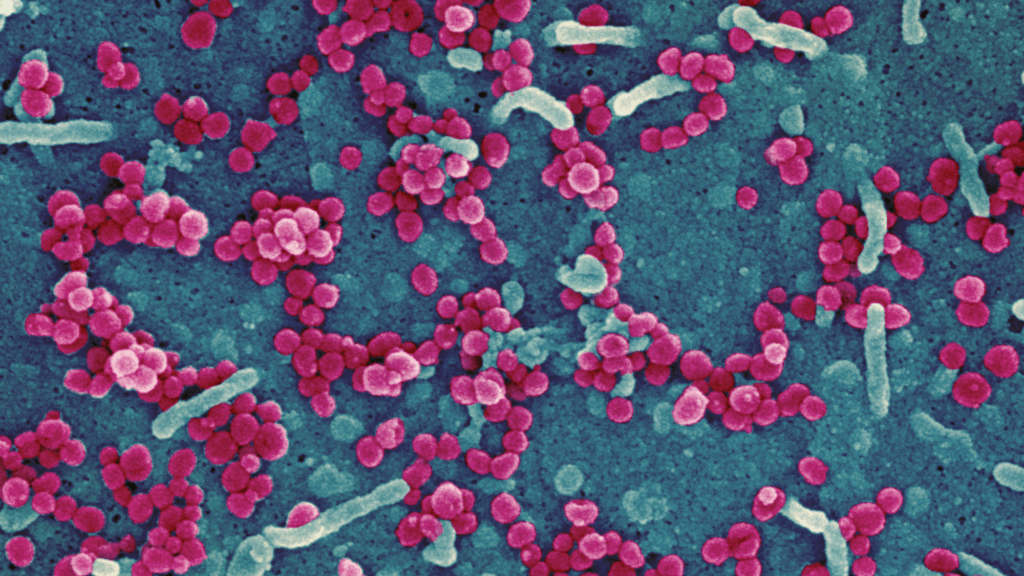

Lassa fever is caused by LASV, an emerging zoonotic virus in the Arenaviridae family of highly pathogenic viruses that can cause severe hemorrhagic fever in humans. Symptoms include hemorrhage, vomiting, swelling of the face, and pain in the chest, back, and abdomen, shock from blood loss, and even death. The disease was first identified in 1969, when four missionary nurses died from a hemorrhagic illness in the town of Lassa, in northeastern Nigeria. Today the disease is known to be endemic in Benin, Ghana, Guinea, Liberia, Mali, Nigeria and Sierra Leone, and probably exists in other West African countries too.

The current disease burden is underestimated. Conservative figures estimate up to 500,000 cases and at least 5,000 related deaths each year. The overall case fatality rate for adults is estimated to be 1%, but among those hospitalized with severe disease, this rises to at least 15%. One recent study estimated that 2.1–3.4 million human LASV infections occur annually throughout West Africa, resulting in 15,000–35,000 hospitalizations and 1,300–8,300 deaths.

LASV is most commonly transmitted to humans from an infected rodent known as the multimammate rat (Mastomys natalensis). This type of rat is found throughout sub-Saharan Africa, but currently only West African multimammate rats are known to carry LASV. The rats carry LASV in their urine and excrement, which contaminates areas where food is prepared or stored. There is also some evidence that LASV can be carried by other rodent species.

The virus can also spread from person to person via bodily fluids. Nigeria, Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea are most affected, but increasingly, neighboring countries are experiencing their own emerging outbreaks, with travelers occasionally carrying infections to other regions. If patients are asymptomatic, they usually do not transmit the virus, and the virus is not spread through casual contact such as hugging or shaking hands.

Symptoms can take three weeks after infection to appear, and about three-quarters of people with infections experience only mild symptoms, including light fever and headache, and may not be diagnosed with Lassa fever. About one in five infections result in severe disease, where the virus affects organs including the liver, spleen and kidneys, and causes serious symptoms such as bleeding, vomiting, facial swelling, and difficulty breathing. About one-third of patients also suffer from hearing loss, which can be permanent. Death usually occurs within two weeks of the disease first appearing.

Lassa fever often goes undiagnosed because outbreaks typically occur in locations where laboratory testing capacity is very limited. The disease also closely resembles other endemic illnesses such as malaria and yellow fever in its early stages. However, several confirmed outbreaks of Lassa fever have occurred in the last few years, notably in Nigeria and Ghana. By the end of June 2025, Nigeria recorded 790 laboratory confirmed cases from at least 6109 suspected cases, and 148 confirmed deaths. In 2024, Nigeria recorded over 1,300 confirmed cases and over 10,000 suspected cases, with 214 confirmed deaths.

There have also been isolated reports of travelers returning from endemic areas to the U.S. and Europe infected with LASV (although subsequent testing has sometimes proved negative).

People usually become infected with LASV by coming into contact with substances which have been contaminated by infected rodents – such as by eating food which rats have touched, by handling objects which rats have been in contact with or urinated on, or by cleaning animal droppings. This means almost anyone who handles food or lives in a contaminated area is at risk.

The virus is not transmitted via casual contact such as hugging an infected person but can be spread via the bodily fluids of an infected person. This means health workers caring for people infected with Lassa fever are at a high risk of catching the virus themselves. Use of good personal protective equipment and strict isolation protocols are essential.

Pregnant women are at particular risk from the disease. According to the WHO, among women who contract Lassa fever during the third trimester of pregnancy, the combined mortality rate for both mother and child can exceed 80%.

Experts say the geographic area vulnerable to Lassa fever is growing due to climate change.

Therapeutic options are severely limited. Some patients are treated with ribavirin, an antiviral drug, but researchers remain uncertain about its efficacy and dosing. Many patients receive only supportive care, including rehydration, rest, and treatment of symptoms.

No vaccine is currently available. A recent study by the University of Oxford estimated that vaccinating high-risk populations against LASV could avert up to 4,400 deaths in West Africa per year and save societal costs of almost US$128 million per year, including labor losses and healthcare expenditure.

Several vaccine candidates are in development. One promising candidate is currently being developed by IAVI and partners in West Africa, Europe, and the U.S. This is a single-dose vaccine formulation, based on the modification of an attenuated or weakened strain of vesicular stomatitis virus, which is re-engineered to display the LASV surface protein that plays an essential role in establishing a viral infection. Read our fact sheet.

The same vector platform has already been used to create ERVEBO®, Merck’s single-dose Ebola virus vaccine, which has been widely licensed as safe to use in more than a dozen countries, and has already been used to control Ebola outbreaks in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI)-funded Phase 2a IAVI C105 clinical trial is studying the vaccine in approximately 612 participants at clinical research partner sites in Nigeria, Liberia, and Ghana. Should the candidate be found to be safe and efficacious in clinical testing, IAVI and our partners are committed to making the vaccine affordable and accessible to all populations in need. Development of the vaccine has been funded by CEPI and the European & Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership (EDCTP), with trials conducted in partnership with organizations including the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control and Prevention and the Nigeria Lassa Vaccine Taskforce.

You can read more about IAVI’s LASV vaccine development efforts here.

Mastomys rats are so abundant in West Africa that eliminating them from residential areas is impossible. However, in domestic settings, Lassa fever can be prevented by rigorous rodent control and hygiene, including storing food in rat-proof containers, sealing garbage and setting rat traps. In healthcare settings, full PPE plus strict isolation and sterilization protocols are essential.