September 12, 2025

Frequently asked questions: Sudan virus disease

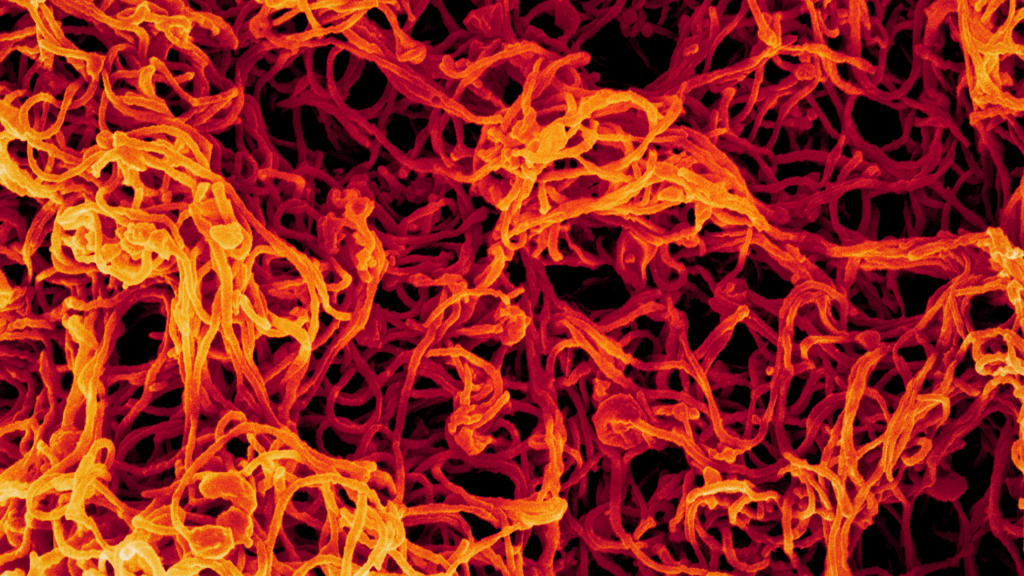

Learn more about Sudan virus, a filovirus that causes severe hemorrhagic illness in humans.

Exactly what is Sudan virus disease (SVD)? In January 2025, Uganda reported an outbreak of SVD, a cousin to Ebola that causes a severe, often fatal illness with a high case fatality rate that is a risk to global health security. Nine outbreaks of SVD have been reported in sub-Saharan Africa since the discovery of the causative agent, Sudan virus (SUDV), in 1976. Due to its high case fatality rate and high potential to cause a public health emergency of international concern, SUDV is priority pathogen for which IAVI and our partners are developing a single-dose vaccine candidate as part of our emerging infectious disease (EID) vaccine development program. We have also contributed to SVD outbreak reponses in Uganda. Read more about our SUDV vaccine development program.

Frequently asked questions

The pathogen SUDV (Orthoebolavirus sudanense) causes SVD – a severe, often fatal, viral hemorrhagic fever – in humans and nonhuman primates. The virus is endemic to sub-Saharan Africa and has caused nine recorded outbreaks in the region since its identification in Southern Sudan in 1976. Fruit bats are likely the natural host for SUDV.

The term “Ebola disease” is often used to describe the severe illness caused by a group of viruses called orthoebolaviruses. SUDV is one of six genetically distinct orthoebolaviruses, four of which are known to cause disease in humans. Previously called “Sudan Ebolavirus,” the virus received a nomenclature update in 2001 – SUDV for the virus, and SVD for the disease it causes.

SUDV is zoonotic, meaning it originates in vertebrate animals, possibly fruit bats. The virus is transmitted to humans when they come in contact with animals that are natural reservoirs for SUDV. This process is known as “zoonotic spillover.” The virus can also be transmitted between humans via direct contact with a symptomatic person or their infectious bodily fluids. Infection from touching the bodies of the recently deceased is also common. Pregnant people infected with the virus can transmit the virus to their fetus, and breastfeeding women can transmit the virus to their babies via breastmilk. Even after a patient has recovered from acute illness, the virus can persist for weeks in certain bodily fluids despite virus clearance from the blood.

Once a person is infected with SUDV, the incubation time before symptoms appear is two to 21 days. Initial symptoms can be nonspecific and similar to influenza or other endemic illnesses and include fever, aches, and pains, and may progress to include nausea, diarrhea, and/or vomiting. In severe cases, patients may experience bleeding from multiple sites internally or externally, shock, and multiple organ failure and may require blood transfusions. Infected pregnant people may experience spontaneous abortion (miscarriage).

SVD may present similarly to other infectious diseases, and so early detection is crucial. Infection must be confirmed using a laboratory blood test.

Acute illness typically lasts for one to two weeks, and in fatal cases, death occurs between one to three weeks after symptom onset. For survivors, recovery can be prolonged, with many experiencing persistent health issues for weeks or even months after the virus clears.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), nine total confirmed outbreaks of SVD have occurred in sub-Sharan Africa since 1976. An outbreak that ran from January to April of 2025 marks Uganda’s sixth known SVD outbreak. The case fatality rate for SVD has ranged from 41% to 100% in previous outbreaks.

The WHO cites “family members, healthcare workers, and participants in burial ceremonies with direct contact with the deceased” as facing an elevated risk of infection. Others who may also have an elevated risk of infection include people who have recently traveled to an area with an active outbreak, close contacts of people infected with SUDV, laboratory workers, and those who hunt and/or consume wild animals (“bushmeat”). Pregnant people also may face an increased risk of severe disease compared with the general population.

No licensed vaccines or therapeutics are available for SVD, and existing Ebola vaccines are not effective against SVD. Treatment has been limited to supportive care, such as administration of fluids, blood pressure management, pain and fever control, oxygen therapy, and treatment of secondary infections. In January 2025, health authorities began testing remdesivir, a broad-based antiviral that reduces severity and mortality of SARS-CoV-2 infection, for efficacy in people infected with SUDV in Uganda alongside an investigational vaccine candidate as part of a comprehensive public health response.

Around two dozen SUDV vaccine candidates are in development, including a single-dose vaccine candidate in development by IAVI and our partners. In 2025, IAVI provided the WHO with doses of its investigational SUDV vaccine candidate for use in a ring vaccination trial as part of Uganda’s comprehensive public health response to its SVD outbreak.

You can read more about IAVI’s SUDV vaccine development efforts and our contributions to Uganda’s SVD outbreak response here.

In the absence of a vaccine, SVD poses a serious public health risk, and so infection control and prevention measures are critical. In areas where SUDV is endemic, a combination of community engagement and health systems strengthening that emphasizes safe burial practices and avoiding bushmeat consumption is key. These efforts are underpinned by disease surveillance efforts by the WHO and national health authorities. However, more coordinated action and investment are needed to develop effective medical countermeasures that can either prevent an outbreak altogether or stop an active outbreak in its tracks.

https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2025-DON555

https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ebola-virus-disease

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0929664623002292

https://www.microbiologyresearch.org/content/journal/jgv/10.1099/jgv.0.001864

https://www.cdc.gov/ebola/about/index.html

https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/31/2/24-0983_article